Before you can truly understand if the odds you’re getting are good or not you need to understand how bookmakers set their odds.

It’s not as simple as you might think and once you understand the process it’s much easier to identify value bets.

There are two key concepts you need to be aware of, that we’ll cover in this article, and they are determining true odds and how bookmakers adjust their odds to make a profit.

Commission = (1 – (1 / 1.042). 100%. Commission = (1 – 0.96). 100%. Commission = 4%. So in this example, for every £100 that you bet, you are paying an average of £4 to the bookmaker. Or in other words, at a commission rate of 4%, you would be offered odds of 1.92 on a coin toss. A good business plan for a bookmaker’s office consists of several sections: introduction, marketing, commercial and organisational blocks, requirements for registering a legal entity, and conclusion. The financial section contains comprehensive information on the cost of launching the project and the expected profit margins. The amount of investment directly depends on whether the entrepreneur.

Key Points

Setting The Odds: 'Pricing Up' the Market. A bookmaker will first of all price up the 'real' chance of an event i.e to 100% and then alter the prices for the in-built margin he has established for the type of event. For example, let's consider an international football match, England vs France.

- When setting odds for an event, a bookmaker’s main aim is to try to ensure that they will make a profit no matter what the outcome.

- Bookmakers will first research and attempt to determine the true odds of any outcome occurring.

- Actual odds offered to punters will be based upon those true odds but downwardly adapted so as to provide the bookmaker with a ‘margin’, ‘overround’ or ‘vigorish (vig)’.

- If punters bet in a manner divergent from the bookmaker’s expectations, odds will be adjusted in order to try to maintain that margin.

Setting Odds: Determining True Odds

The first step for any bookmaker in setting their odds for a given event is trying to determine the true probability or odds of any given outcome occurring. What we mean by outcome, in this case, is any possible result that they may have to pay out on (e.g. a home win, a draw or an away win in the case of a football match).

Factors to consider:

In order to determine these true odds, bookmakers will look at factors such as prior form, statistics, historical precedents, expert opinion and any number of other such factors that could impact the event in question. Following this research and analysis, the bookmaker will be left with what they deem to be the most accurate possible true odds of any outcome occurring.

A ‘Fair Book’:

To continue the football match analogy we alluded to earlier, those true odds might be that a home win is evens, a draw is 2/1 and an away win is 5/1. What those odds represent are a 50% chance of a home win, a 33.33% chance of a draw and a 16.67% chance of an away win.

If the bookmaker were to offer those odds, therefore, they would have produced what’s known as a ‘fair book’. That is a betting market where the percentage chances of all of the outcomes add up to exactly 100%.

If in total punters bet in the same proportion as the relative probabilities of each outcome occurring (i.e. 50% on a home win, 33.33% on a draw and 16.67% on an away win) in this example, however, the bookmaker will pay out exactly what they take in regardless of the final result.

Bookmakers, therefore, must adjust the odds they actually offer to punters in order to try to ensure they make a profit.

How Do Bookmakers Actually Set Their Odds?

Once a bookmaker has determined what they believe to be the true odds of any outcome occurring in a given event, they will then adjust those odds downwards before offering them to punters.

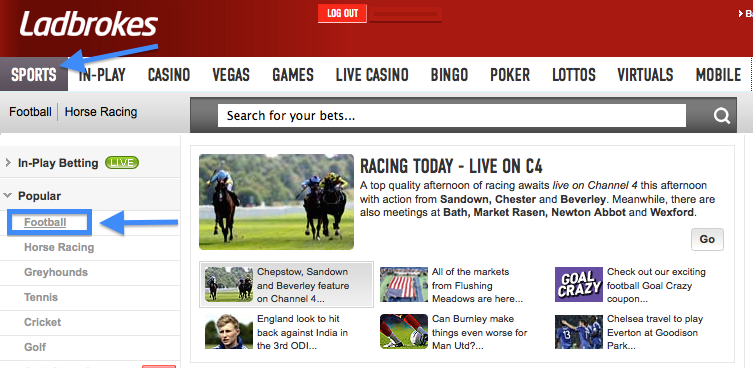

How To Start An Online Bookmakers

In practice, the methods by which bookmakers do this can be diverse and quite complicated but for the sake of our explanation we will focus upon the simplest possible method; proportional decreasing.

In our above example the relative probability of each of the outcomes occurring (50%, 33.33% and 16.67%) has a proportional relationship of 3:2:1. That means that another set of three odds figures with the same relationship but which are all shorter could be what a bookmaker chooses to offer to punters.

An example of such a set of odds is 4/6, 6/4 and 4/1, which equates to relative probabilities of 60%, 40% and 20%. Whilst the proportional relationship between these odds is the same, however, the sum of their percentage figures is 120% rather than 100%. That means that if punters bet according to the same pattern as the true odds the bookmaker has determined (3:2:1), the bookmaker will always receive 20% more than they pay out.

That 20% figure is what is known as the bookmaker’s ‘margin’, ‘overround’ or ‘vigorish/vig’.

How Much Money Do You Need To Start A Bookmakers

Why Do Odds Change Before an Event?

Whilst the above represents a simplified yet accurate representation of the odds setting process in theory, in practice any number of things can cause a bookmaker to need to alter their odds. The most notable example of something which can require a bookmaker to make such changes is us; the punters.

How Does Betting Affect Bookmaker Odds?

As we’ve mentioned above, the margin which the bookmaker attempts to build into every market they set odds for, is based upon the premise that punters will bet in similar proportions to the true odds of the event’s outcomes which they have determined. If in practice, however, punters actually bet far more than a bookmaker expects on one particular outcome then the amount the bookmaker will have to pay out in the event of that outcome (known as their liability) changes.

Example…

To take our previous example, once again, if a bookmaker offers odds of 4/6, 6/4 and 4/1 and takes a total of £120 in stakes, they would expect £60 to be placed at 4/6, £40 at 6/4 and £20 at 4/1. In that case, they would only ever be required to pay out £100 of the total £120 in stakes.

If the pattern were reversed and £60 was placed at 4/1, however, the bookmaker would be required to pay out £300 and so would lose £180. It is when betting patterns differ from what is expected, therefore, that bookmakers alter pre-event odds in order to balance their books and maintain their theoretical margin for the event.

It’s not always possible but changing the odds to balance liability is the main reason bookmaker odds change after the initial prices have been set.